Prior to the WRRC’s 2021 Annual Conference, Tribal Water Resilience in a Changing Environment, I penned an essay entitled “On the Meaning of Water Resilience.” The concept of resilience is ubiquitous in conversations and the literature on water challenges. I questioned whether any of the commonly used definitions captured the Indigenous view of resilience. I highlighted key words from some of the cited definitions: adapt, reorganize, capacity, functions, sustainable, lifestyle, future. I noted: “Water resilience is not only about supply. It is about how the natural and human-connected systems live with the water. Perhaps a term to think about is coexistence: how we as humans co-exist with our natural water systems. Our ability to be resilient requires us to think about this co-existence in everything we do, including how we build and design our communities and their structures.” And I invited the reader to attend the conference, held virtually August 30 through September 1, 2021.

Post-conference, I now invite the reader to listen to the remarks of the outstanding speakers and panels. All sessions were recorded and are freely available. Speakers shared insightful perspectives on water and community resilience. Combining traditional knowledge with science contributes to resiliency. Conveying traditional knowledge from generation to generation enables resiliency. The active exercise of sovereignty is necessary for community resiliency. And so much more was explored.

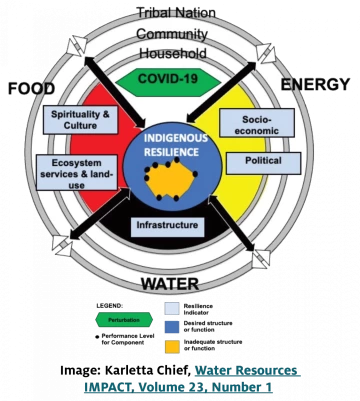

Dr. Karletta Chief stated that Indigenous resilience is “the ability to survive and maintain livelihood.” She observed that Indigenous views of resilience differ across peoples, and Indigenous resilience is multi-layered. Neocolonial practices fail to acknowledge Indigenous strengths. As a corrective, Indigenous resilience discussions should focus now on how Indigenous communities can achieve resilience, that is, how they can survive and maintain their livelihoods and traditions, taking into consideration socioeconomics, politics, infrastructure, ecosystem services and land use, and spirituality and culture.

The themes and concepts introduced by Dr. Chief were reinforced throughout the conference. Speakers emphasized intergenerational teachings and awareness of the needs of others. All generations, especially Elders, have a role in educating the youth. Sharing knowledge and perspectives with non-tribal stakeholders must occur as well. Having Tribes at the table for policymaking, planning, and problem solving expands understanding of needs and solutions. Tribal participation can help people identify how neighbors can help neighbors overcome challenges.

Concern for Mother Earth being out of balance and efforts to address this imbalance were considered. Emphasized concepts included restoration, conservation, water reliability, partnerships, legal frameworks, self-sufficiency, self-determination, technology, data, and culture. Toughness and strength, coping, adaptability, recovering, and shared responsibility were cited as important factors for resilience.

Personal health and river health are connected. As most readers know and discussed in my August Reflections, the Colorado River’s health is poor. Amelia Flores, Chairwoman of the Colorado River Indian Tribes, spoke of our obligation to the

Colorado River: “Our Creator provided the River to take care of us. Now we must do all … we can do to take care of the River.”

Whether virtual or in person, WRRC conferences are designed to provide opportunities for meaningful and respectful dialogue and learning. I recently asked David Eduardo Morales, a new graduate student assistant at the WRRC and first-year student in the master’s program in hydrology, to review the conference sessions and highlight for me comments related to resilience. David offered an excellent summary of his take-aways regarding tribal resilience, which I provide to you as evidence that we are doing our job as educators: Indigenous resilience is, ultimately, the ability for communities to survive and maintain their livelihoods. This ability is reinforced through tribal sovereignty, which itself is a function of a community’s self-determination and self-sufficiency. Indigenous resilience is conceptualized differently from land to land; however, identifying Indigenous resiliency frameworks that incorporate Indigenous perspectives will facilitate the measuring and evaluation of resiliency. A fundamental aspect of resilience is understanding others’ needs. This understanding is strengthened across generations through the collecting and teaching of traditional knowledge and teachings. Resiliency is not a given quality, but a state of being. It seems to be widely agreed that challenges promote resiliency, and [from] this acknowledgement stems the call for collaboration across Tribal Nations. Indigenous resilience focuses not on the mitigation of risks, but on a community’s ability to withstand and adapt to … shocks and difficulties.

I invite your take-aways from the conference and/or perspectives on Indigenous water resilience. Please email me anytime at smegdal@arizona.edu.

We respectfully acknowledge the University of Arizona is on the land and territories of Indigenous peoples. Today, Arizona is home to 22 federally recognized tribes, with Tucson being home to the O’odham and the Yaqui. Committed to diversity and inclusion, the University strives to build sustainable relationships with sovereign Native Nations and Indigenous communities through education offerings, partnerships, and community service.